If you’ve ever looked at a crop rotation diagram in a gardening book and felt completely bamboozled, then you’re not alone. But crop rotation doesn’t have to be taxing, and getting to grips with it brings a whole host of benefits to the vegetable garden. For the organic gardener, crop rotation is one of the main weapons in your arsenal against problematic pests and diseases.

At its simplest, crop rotation is simply ensuring that you don’t grow the same crops in the soil year after year. Doing so signposts their location to every pest in the garden, allowing an army to build up to attack plants every summer.

…moving crops around can help keep the weeds under control… moving crops around means that no particular weed gains the upper hand.

Diseases can take hold in the soil as well, meaning that plants don’t stand much of a chance. When you grow the same crops in the same soil every year you create a monoculture in time, even if your planting is diverse and you don’t have a spatial monoculture.

As well as confusing pests and limiting diseases, moving crops around can help keep the weeds under control. Different plants cover the ground in different patterns, and some of them (such as potatoes) can completely shade the soil underneath them and discourage the growth of weeds. Conversely, some plants make it difficult to spot similar-looking weeds, or to gain enough access to deal with them; moving crops around means that no particular weed gains the upper hand.

Different crops have different nutritional requirements and take those nutrients from different levels in the soil – some plants are far more deep-rooted than others, some fix nitrogen in the soil, whilst others are heavy feeders and can benefit from this. Moving them around the plot means that no one area of soil will become exhausted.

So now that we know why a crop rotation is a good idea, how do we go about putting one in place?

- The first step is to make a list of all the crops you want to grow; it helps if you have a rough idea of how much space each one will take up.

- The second step is to group those crops together, according to the plant family to which they belong (related plants often share growing requirements, and are susceptible to the same pests and diseases).

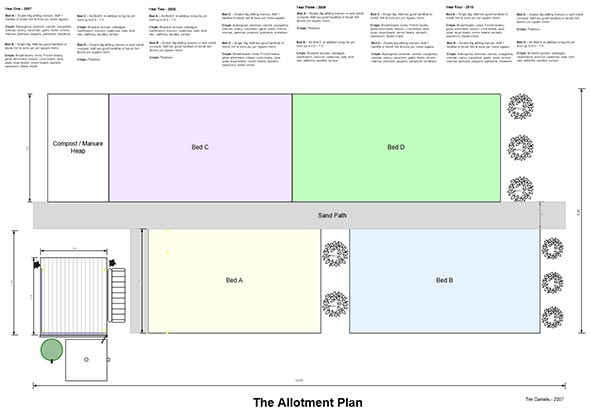

- Use this list and keep a record of where you plant each group of crops each year. It helps to draw a diagram of your beds including dimensions if there are no obvious boundaries.

There are four main families of crops that can be grouped together and rotated as follows:

1. Legumes

Legumes like to have deeply dug soil with added manure or garden compost. They are good at fixing nitrogen from the air into nodules on their roots. Snipping their roots off and digging them into the soil once plants have finished cropping will make the nitrogen available to the next crop.

The legume family includes peas as well as broad, runner and French beans.

2. Brassicas

Are heavy feeders and will perform well with the additional nitrogen that was fixed into the soil by legumes. It is better not to add manure or compost to the soil before growing brassicas but they do benefit from lime which can prevent club root.

There are a lot of members of the brassica family, including cabbages and cauliflowers, Brussels sprouts and swede, land cress and Chinese cabbage, kale and broccoli, turnips and radishes.

3. Root Crops and Tubers

Root crops are often grouped together for the purposes of a rotation, but come from different families.

Carrots are related to parsnips, celery and celeriac, parsley and fennel. Beetroot is closer to leafy vegetables – it’s in the same family as chard, leaf beet and spinach.

Tomatoes, peppers, aubergines and potatoes are all related, although peppers and aubergines need more heat and are usually grown in the greenhouse (and don’t get late blight, which can devastate potatoes and tomatoes).

Melons and watermelons are related to courgettes, squash and pumpkins, although you wouldn’t grow them all in the same place as melons need far more heat.

Potatoes are good at clearing weeds from the ground as they are regularly earthed up and their leaves shade out weeds. Potatoes are a hungry crop and like to have some well rotted manure added, although this should not be applied when growing root crops such as carrots and parsnips since the high level of magnesium will cause them to fork.

4. Alliums

Allium seedlings are tricky to weed, and should not be planted in freshly manured soil since there is a link between manure and white rot. Alliums usually follow on from root crops.

Onions, spring onions, leeks, garlic and shallots are all alliums.

Other Crops

Lettuce is often considered to be the odd-one-out when it comes to crop rotation, and it is usually fitted in wherever there is space. But in actual fact it is related to Jerusalem artichokes and sunflowers.

Once you have your crops grouped together, the next step is to divide your plot into convenient beds or sections – preferably one for each group of plants that you want to grow, although it’s at this point that things start to get a little complicated.

A classic allotment rotation, for example, may use four beds and rotate four groups of crops through them over the course of four years. But most people don’t grow equal amounts of potatoes and brassicas, some don’t want to grow onions and some may have a yen for sweetcorn (often left out of examples).

Small beds can give you more flexibility, especially since some summer and winter crops overlap.

The key is to take a pragmatic approach to crop rotation. Once you have your crop list, and have divided up your plot, group your plants together in a way that makes sense to you and your goals – whether it’s reducing pests and diseases, controlling weeds or simply putting crops with similar needs for water together. Then once you have your groups, keep them moving around the plot so that they return to the same soil as infrequently as possible.

The minimum number of years in a cycle is three; four is better and some complicated rotations run to five years or more.

The final stage (before sowing and planting!) is to sort out the soil amendments for your rotation. Well-rotted manure is usually added at the end of the growing season, to get a bed ready for a crop of hungry plants like potatoes. Depending on your soil pH, you may also need to add lime to the area in which you’ll be growing your brassicas.

In small spaces, a full crop rotation may be overkill. Instead, you might like to try following the Square Foot Gardening system, in which you divide your vegetable bed into square foot (or square metre) sections.

Each section is planted up with a different crop (paying careful attention to the plant spacing). As each crop is harvested, the square is replanted with something different that has been waiting in a seed tray for the space to become available. Because the crops are constantly moving around, Square Foot Gardening takes care of crop rotation for you, whilst providing small harvests of a large variety of crops throughout the year, and avoiding gluts. You can use some of the squares to plant flowers to attract beneficial insects to the garden, which will help prevent pest problems.

Another advantage of Square Foot Gardening is that it lends itself to little bursts of gardening activity whenever you have the time – you won’t have to spend hours weeding a big plot all in one go.

The final point to note is that many common weeds belong to the same family as some crop plants, and can harbour the same pests and diseases.

So don’t let a weedy plot undo all the hard work you’ve put in to your crop rotation!